In 2014 a small glacier in the center of Iceland was found to be dead.

It was not the glacier I write about in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk, whose looming presence inspired wild thoughts in me, and might have lured me to my death if I were more naïve about Icelandic nature. That was Hofsjökull.

It was not my favorite glacier, the beauty who appears, unpredictably, across 75 miles of bay from Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavik, the glacier Icelandic author Halldor Laxness called “a soul clad in air.” That glacier, Snæfellsjökull, occupies several chapters in Looking for the Hidden Folk.

The dead glacier, Ok, meaning “yoke” or “burden,” was their little brother. A white tooth on a medium-tall mountain, Ok was a landmark on an ancient road, but exceptional in Iceland only for his small size.

At his greatest, Ok’s ice covered six square miles.

Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, covers more than 3,000 square miles.

A glacier is made when snow falls faster than it melts. At 65 feet deep, the snow starts turning to ice. At a hundred feet deep, the ice begins to creep. It flows at a rate of three feet a day downhill. Its melting edge is called its mouth. When ice breaks off into the meltwater lake, the glacier is said to calve.

A glacier that does not creep or calve is dead.

Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer heard of the death of Ok in 2016. “As cultural anthropologists”--the two work at Rice University in Houston--“we could see that people were implicated in the loss of glaciers in at least two ways,” they wrote. One: Humans were hurting the planet. Two: Humans were hurting themselves, “especially in a country like Iceland whose identity is so bound up with glaciers.”

So they made a film. Then they planned a funeral.

They asked Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason to design a memorial plaque. “How do you write a eulogy,” he asked, “for a symbol of eternity?”

On August 18, 2019 a few dozen people climbed Ok. There was no path. They passed from moss to lichens to “jagged stones,” they slipped on ice and sank into icy puddles. It was a harder climb than many had expected. The wind bit. It took three hours.

They were asked to hike in silence, not looking back, as if they were hiking up Helgafell, a small hill I frequently climb in West Iceland whose name means Holy Mountain and whose legend says surmounting it silently, without looking back, will grant you three wishes.

At the top of Ok, the hikers read out the glacier’s death certificate. Cause of death? “Excessive heat” and “humans.” They affixed the bronze plaque to a rock; addressed to the future, it says, “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Then they began to sing.

The funeral, Howe and Boyer wrote in Anthropology News, “was a media event covered in nearly every country in the world.” The story of Ok “seems to have humanized climate change for a lot of people. It put a face and a name to an abstract problem.”

In 1992 I attended a lecture by Gillian Overing, then an English professor at Wake Forest University, during the International Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo, Michigan. In Iceland, Overing noted, the center is the margin. Geography is inside-out. People settle on the temperate edges of the island, while its interior is a glacial desert, cold, inhospitable, and not even crossable most of the year. “What kind of self,” she mused, “might these places reflect?” What kind of self has wilderness at its heart?

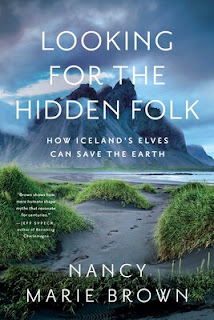

That question, that concept, in large part, inspired my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth.

But now, with the death of Ok, a new question arises: What happens to the self when the wilderness in its heart is dead?

“Help us,” wrote Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, in The New York Times, “keep the ice in Iceland.”

We no longer even know how to talk about nature, writes George Monbiot in The Guardian. We use terms that are “cold and alienating,” like reserve. “Think of what we mean when we use that word about a person,” he says. The word environment “creates no pictures in the mind.” Calling plants or animals “resources” or “stocks” implies “they belong to us and their role is to serve us.” Language has power, Monbiot reminds us. “Those who name it own it,” he argues, concluding: “We need new words.”

Or, perhaps, a new look at some very old ones, like elf.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth was published October 4 by Pegasus Books. Order it at your favorite bookshop, through Simon & Schuster distributors, or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Thanks!

For another artist's response to the funeral for Ok glacier, see this news release from Rice University.

Wanderer, storyteller, wise, half-blind, with a wonderful horse.

By Nancy Marie Brown

Showing posts with label Iceland. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Iceland. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 5, 2022

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Writing for Iceland

Interviewing me about my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, a reporter asked, Did you write it for an Icelandic audience, or for an American one?

Um ... yes.

Of course, my main audience is the much larger American one. I fell in love with Iceland (population 365,000) on my first visit, in 1986, and much of my writing since then has been aimed at sharing my love for Iceland's landscape and culture with people who haven't (yet) visited this amazing island in the north Atlantic. (In 1986, Iceland was not on everyone's bucket list, as it seems to be today.)

But it is also very important to me that the Icelanders I am writing about like my books--or at least see them as being fair. It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out.

So when my book about Iceland's elves, Looking for the Hidden Folk, was sent to a group of Icelandic writers and scholars for review, pre-publication, I was anxious that they would also think I was being fair to their ancient culture.

I needn't have worried.

Wrote Egill Bjarnason, author of How Iceland Changed the World: The Big History of a Small Island: "Nancy Marie Brown reveals to us skeptics how rocks and hills are the mansions of elves, or at least what it takes to believe so. Looking for the Hidden Folk evocatively animates the Icelandic landscape through Brown's past and present travels and busts some prevalent clichés and myths along the way--this book is my reply to the next foreign reporter asking about that Elf Lobby."

Terry Gunnell, a professor of folkloristics at the University of Iceland, whose work on elf-lore is heavily cited in the book, called it "A love song to the living landscape of Iceland and the cultural history in which it is clothed, inspired by the author's numerous encounters with the country and its people over the last decades."

Ármann Jakobsson, a professor in the department of Icelandic at the University of Iceland, and author of the fascinating book The Troll Inside You, also understood what I was trying to say. He wrote: "Looking for the Hidden Folk is an elegantly written and wonderfully individualistic exploration of Icelandic culture through the ages, combining a shrewd appraisal of traditions with an acute interest in the modern world and all its intellectual quirks." Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view."

And finally, my friend Gísli Pálsson, professor of anthropology at the university of Iceland, seems to always know how to sum up my books just so. He wrote: "This is a sweeping and moving journey across time and space—through myth and theory, language, and literature—into the world of wonder and enchantment. Beautifully written, Looking for the Hidden Folk offers a compelling and surprising case for the recognition of forces and beings not necessarily 'seen' in everyday life but nevertheless somehow sensed, exploring their complexity and why they matter."

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Um ... yes.

Of course, my main audience is the much larger American one. I fell in love with Iceland (population 365,000) on my first visit, in 1986, and much of my writing since then has been aimed at sharing my love for Iceland's landscape and culture with people who haven't (yet) visited this amazing island in the north Atlantic. (In 1986, Iceland was not on everyone's bucket list, as it seems to be today.)

But it is also very important to me that the Icelanders I am writing about like my books--or at least see them as being fair. It makes me very happy, for instance, to know that the families featured in my first book, A Good Horse Has No Color: Searching Iceland for the Perfect Horse, are always glad to have me visit. This summer, 25 years after I bought a horse from them, I spent a week with Fjóla and Elvar of the farm Syðra-Skörðugil in north Iceland; we laughed at how naive I'd been about horses then, and reminisced over how well things had turned out.

So when my book about Iceland's elves, Looking for the Hidden Folk, was sent to a group of Icelandic writers and scholars for review, pre-publication, I was anxious that they would also think I was being fair to their ancient culture.

I needn't have worried.

Wrote Egill Bjarnason, author of How Iceland Changed the World: The Big History of a Small Island: "Nancy Marie Brown reveals to us skeptics how rocks and hills are the mansions of elves, or at least what it takes to believe so. Looking for the Hidden Folk evocatively animates the Icelandic landscape through Brown's past and present travels and busts some prevalent clichés and myths along the way--this book is my reply to the next foreign reporter asking about that Elf Lobby."

Terry Gunnell, a professor of folkloristics at the University of Iceland, whose work on elf-lore is heavily cited in the book, called it "A love song to the living landscape of Iceland and the cultural history in which it is clothed, inspired by the author's numerous encounters with the country and its people over the last decades."

Ármann Jakobsson, a professor in the department of Icelandic at the University of Iceland, and author of the fascinating book The Troll Inside You, also understood what I was trying to say. He wrote: "Looking for the Hidden Folk is an elegantly written and wonderfully individualistic exploration of Icelandic culture through the ages, combining a shrewd appraisal of traditions with an acute interest in the modern world and all its intellectual quirks." Gísli Sigurðsson, a research professor at The Árni Magnússon Institute of the University of Iceland, agreed. He wrote: "Using ideas and stories about the hidden folk in Iceland as a stepping stone into the human perception of our homes in the world where stories and memories breathe life into places, be it through the vocabulary of quantum physics or folklore, Nancy Marie Brown makes us realize that there is always more to the world than meets the eye. And that world is not there for us to conquer and exploit but to walk into and sense the dew with our bare feet on the soft moss, beside breathing horses and mighty glaciers in the drifting fog that often blocks our view."

And finally, my friend Gísli Pálsson, professor of anthropology at the university of Iceland, seems to always know how to sum up my books just so. He wrote: "This is a sweeping and moving journey across time and space—through myth and theory, language, and literature—into the world of wonder and enchantment. Beautifully written, Looking for the Hidden Folk offers a compelling and surprising case for the recognition of forces and beings not necessarily 'seen' in everyday life but nevertheless somehow sensed, exploring their complexity and why they matter."

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

What Does It Mean to Believe in Elves?

Icelanders believe in elves. There are many ways you could take issue with that sentence, but let's start with that shapeshifting verb, “to believe.”

We believe in elves, we believe in gravity, we believe in science, we believe in God. Does anyone really know what it means to believe?

As I note in my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, anthropologists like himself, Rodney Needham wrote in 1972, “appear to take it for granted that ‘belief’ is a word of as little ambiguity as ‘spear’ or ‘cow’” when they write about the beliefs of this culture or that.

Yet “belief” is kaleidoscopic. It translates a “bewildering variety” of foreign terms. Its root means to love or desire. Translators of the Bible used it to translate trust or obey. It means to follow a religion, to accept a statement as true, or to hold an opinion. You can say, “I believe I’ll have fish for dinner” as easily as “I believe in elves” or “I believe in God.”

Philosopher David Hume in 1739 defined belief as “something felt by the mind, which distinguishes the ideas of the judgment from the fictions of the imagination.”

Stuart Hampshire in 1959 defined a man’s beliefs as “the generally unchanging background to his active thought,” those things he “never had occasion to question” or to state.

Jonathan Lanman in 2008 defined belief as “the state of a cognitive system holding information (not necessarily in the propositional or explicit form) as true in the generation of further thought and behavior.” Using this definition, Lanman asserted, we can “pursue a cross-cultural science of belief,” as everyone has such beliefs. “All have cognitive systems that represent the world in some way and act according to what they believe to be true about that world.”

Your beliefs define you. As fuzzy, illogical, or unquestioned as they may be, they control how you see the world and how you act in response.

As Needham concluded, “An assertion of belief is a report about the person who makes it, and not intrinsically or primarily about objective matters of truth or fact.” Belief, said Needham, is “ultimately a reference to an inner state.” More, that inner state seems to be emotional. Yet we cannot say, in English at least, that someone is “believing” or “belief-full,” Needham mused.

Philosopher Jesse Prinz thinks the emotion involved is wonder. It’s wonder that produces both religion and science, as well as art: The three institutions “that are most central to our humanity,” said Prinz, are “united in wonder.” They are not in conflict. They are not either/or. Each of the three feeds “the appetite that wonder excites in us,” says Prinz. Each allows us “to transcend our animality by transporting us to hidden worlds.” It’s wonder, Prinz argues, that makes us human.

Adam Smith, the inventor of capitalism, wondered about wonder in 1795, Prinz found. “He wrote that wonder arises ‘when something quite new and singular is presented … [and] memory cannot, from all its stores, cast up any image that nearly resembles this strange appearance.’”

What is it like? the brain asks. Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

Wonder is sensory: “We stare and widen our eyes,” wrote Prinz. Wonder is cognitive: “Such things are perplexing because we cannot rely on past experience to comprehend them … : We gasp and say ‘Wow!’” And then there is “a dimension that can be described as spiritual.” Wonder, concludes Prinz, awakens us. “We don’t just take the world for granted, we’re struck by it.”

Or we are not. Emotions, brain researchers have found, depend on culture. You will not sense wonder if you’re never exposed to it.

There’s much we don’t know about the brain. But we know it categorizes. We know it uses concepts and words, finds causes and crafts stories. We know it constantly simulates the world and makes multiple predictions of what we will sense and see—and what we should do in response.

We know that it’s wired for emotion, for wonder, for ecstasy, but that Western culture disdains and derides this side of the brain. We’re taught to control our emotions, to give up wonder in childhood, to stifle our mystical experiences—or at least not to talk about them. Otherwise we’ll be thought “ignorant, eccentric, or unwell,” says Jules Evans of the Centre for the History of the Emotions in London.

We’ll be laughed at as loony elf-seers.

But without words, without the concepts to describe them, you are “experientially blind,” says psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett. Wonders—elves?—may be all around you, but you will not see them.

Which brings up the next question I grapple with in Looking for the Hidden Folk, What immaterial beings are we allowed to believe in, and who is allowed to do the believing?

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

We believe in elves, we believe in gravity, we believe in science, we believe in God. Does anyone really know what it means to believe?

As I note in my book Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, anthropologists like himself, Rodney Needham wrote in 1972, “appear to take it for granted that ‘belief’ is a word of as little ambiguity as ‘spear’ or ‘cow’” when they write about the beliefs of this culture or that.

Yet “belief” is kaleidoscopic. It translates a “bewildering variety” of foreign terms. Its root means to love or desire. Translators of the Bible used it to translate trust or obey. It means to follow a religion, to accept a statement as true, or to hold an opinion. You can say, “I believe I’ll have fish for dinner” as easily as “I believe in elves” or “I believe in God.”

Philosopher David Hume in 1739 defined belief as “something felt by the mind, which distinguishes the ideas of the judgment from the fictions of the imagination.”

Stuart Hampshire in 1959 defined a man’s beliefs as “the generally unchanging background to his active thought,” those things he “never had occasion to question” or to state.

Jonathan Lanman in 2008 defined belief as “the state of a cognitive system holding information (not necessarily in the propositional or explicit form) as true in the generation of further thought and behavior.” Using this definition, Lanman asserted, we can “pursue a cross-cultural science of belief,” as everyone has such beliefs. “All have cognitive systems that represent the world in some way and act according to what they believe to be true about that world.”

Your beliefs define you. As fuzzy, illogical, or unquestioned as they may be, they control how you see the world and how you act in response.

As Needham concluded, “An assertion of belief is a report about the person who makes it, and not intrinsically or primarily about objective matters of truth or fact.” Belief, said Needham, is “ultimately a reference to an inner state.” More, that inner state seems to be emotional. Yet we cannot say, in English at least, that someone is “believing” or “belief-full,” Needham mused.

Philosopher Jesse Prinz thinks the emotion involved is wonder. It’s wonder that produces both religion and science, as well as art: The three institutions “that are most central to our humanity,” said Prinz, are “united in wonder.” They are not in conflict. They are not either/or. Each of the three feeds “the appetite that wonder excites in us,” says Prinz. Each allows us “to transcend our animality by transporting us to hidden worlds.” It’s wonder, Prinz argues, that makes us human.

Adam Smith, the inventor of capitalism, wondered about wonder in 1795, Prinz found. “He wrote that wonder arises ‘when something quite new and singular is presented … [and] memory cannot, from all its stores, cast up any image that nearly resembles this strange appearance.’”

What is it like? the brain asks. Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

Wonder is sensory: “We stare and widen our eyes,” wrote Prinz. Wonder is cognitive: “Such things are perplexing because we cannot rely on past experience to comprehend them … : We gasp and say ‘Wow!’” And then there is “a dimension that can be described as spiritual.” Wonder, concludes Prinz, awakens us. “We don’t just take the world for granted, we’re struck by it.”

Or we are not. Emotions, brain researchers have found, depend on culture. You will not sense wonder if you’re never exposed to it.

There’s much we don’t know about the brain. But we know it categorizes. We know it uses concepts and words, finds causes and crafts stories. We know it constantly simulates the world and makes multiple predictions of what we will sense and see—and what we should do in response.

We know that it’s wired for emotion, for wonder, for ecstasy, but that Western culture disdains and derides this side of the brain. We’re taught to control our emotions, to give up wonder in childhood, to stifle our mystical experiences—or at least not to talk about them. Otherwise we’ll be thought “ignorant, eccentric, or unwell,” says Jules Evans of the Centre for the History of the Emotions in London.

We’ll be laughed at as loony elf-seers.

But without words, without the concepts to describe them, you are “experientially blind,” says psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett. Wonders—elves?—may be all around you, but you will not see them.

Which brings up the next question I grapple with in Looking for the Hidden Folk, What immaterial beings are we allowed to believe in, and who is allowed to do the believing?

You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Icelandic Bliss

In a way, my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland’s Elves Can Save the Earth, is about the power of stories. We all tell stories. We always have. But we don’t always take responsibility for the effects of our storytelling. Stories shape how you see the world. They determine not only how you think of elves, but also how you think of such “real” things as mountains—or creeping thyme.

“When we look at a landscape,” writes Robert Macfarlane in Mountains of the Mind, “we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. … We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. … What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.”

A story that cast a magic spell upon all mountains was Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke, from Ireland, published it in 1757, when he was twenty-eight. He was, writes Macfarlane, “interested in our psychic response to things—a rushing cataract, say, a dark vault or a cliff face—that seized, terrified, and yet also somehow pleased the mind by dint of being too big, too high, too fast, too obscured, too powerful, too something, to be properly comprehended.” Instead, such things inspired “a heady blend of pleasure and terror. Beauty, by contrast, was inspired by the visually regular, the proportioned, the predictable.” It’s the frisson of fear that makes a Icelandic volcano, or a cliffside swathed in fog, sublime. Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.”

I once visited that part of Scotland, the western edge of the Isle of Lewis, but did not meet Campbell walking her moor. Still, a story Macfarlane told, a little aside, gave me a new perspective on Iceland (the most interesting place in the world to me). Macfarlane wrote, “When it wasn’t too cold, and not so dry that the heather was sharp, Anne liked to walk barefoot on the moor. ‘It takes about two weeks to get your feet toughened up so that it’s no discomfort. And then it’s bliss.’ You should try it when you’re out there. Take those big boots of yours off!’” On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far.

Back on the bank, I dabbled my toes and gazed at the glacier-capped volcano, Snaefellsjokull, its corruscations of lava catching the light, until it was time to go, then, remembering Campbell’s bliss, decided to walk barefoot back to the car. It was lovely. The heath was springy and soft and comforting to my feet—though they were not even toughened up. Picking along, carefully placing each foot, I found ripe crowberries and almost ripe blueberries, some very blue but still tart. The grass was soft, too, but I found myself preferentially stepping on the berry bushes and fragrant creeping thyme, which tickled. Who would have thought that thyme (not time) equaled bliss? You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

A story that cast a magic spell upon all mountains was Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke, from Ireland, published it in 1757, when he was twenty-eight. He was, writes Macfarlane, “interested in our psychic response to things—a rushing cataract, say, a dark vault or a cliff face—that seized, terrified, and yet also somehow pleased the mind by dint of being too big, too high, too fast, too obscured, too powerful, too something, to be properly comprehended.” Instead, such things inspired “a heady blend of pleasure and terror. Beauty, by contrast, was inspired by the visually regular, the proportioned, the predictable.” It’s the frisson of fear that makes a Icelandic volcano, or a cliffside swathed in fog, sublime. Burke’s book, says Macfarlane, “provided a new lens through which wilderness could be viewed and appreciated.” Macfarlane’s own books do much the same for me. In The Old Ways, he mentions an archaeologist named Anne Campbell who was “close-mapping” a moor. Why that moor? “It is the most interesting place in the world to me,” she told Macfarlane. “So I spend most of my time walking shieling tracks, paths, and the streams and the walls that used to divide up the land. Then I talk to people and try to fix their memories to those particular places.”

I once visited that part of Scotland, the western edge of the Isle of Lewis, but did not meet Campbell walking her moor. Still, a story Macfarlane told, a little aside, gave me a new perspective on Iceland (the most interesting place in the world to me). Macfarlane wrote, “When it wasn’t too cold, and not so dry that the heather was sharp, Anne liked to walk barefoot on the moor. ‘It takes about two weeks to get your feet toughened up so that it’s no discomfort. And then it’s bliss.’ You should try it when you’re out there. Take those big boots of yours off!’” On the western tip of Iceland’s Snaefellsnes peninsula sits the long-abandoned farm of Laugarbrekka, where Gudrid the Far-Traveler was born in about 982. I’ve written two books about Gudrid, sister-in-law to Leif Eiriksson, the Viking explorer credited with discovering America some five hundred years before Columbus. Yet Gudrid spent more time in the New World than Leif did. Gudrid is the real Viking explorer, and a recurring inspiration to me. In 2016, on a sunny Sunday in late July, I visited her monument at Laugarbrekka for the umpteenth time. I walked out to the laug or bathing pool, which is no longer bathwater warm, took off my boots, rolled up my pants, and waded in, but the sharp stony bottom of the lake kept me from going far.

Back on the bank, I dabbled my toes and gazed at the glacier-capped volcano, Snaefellsjokull, its corruscations of lava catching the light, until it was time to go, then, remembering Campbell’s bliss, decided to walk barefoot back to the car. It was lovely. The heath was springy and soft and comforting to my feet—though they were not even toughened up. Picking along, carefully placing each foot, I found ripe crowberries and almost ripe blueberries, some very blue but still tart. The grass was soft, too, but I found myself preferentially stepping on the berry bushes and fragrant creeping thyme, which tickled. Who would have thought that thyme (not time) equaled bliss? You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

The Remarkable Moníka of Merkigil

The farm of Merkigil in Skagafjörður, north Iceland, is famous for two reasons: 1) the treacherous gorge you had to cross to get there, before the glacial river beside the farm was bridged in 1961; and 2) the grand, two-story concrete house built by the widow Moníka with the help of her daughters—years before the river was bridged.

This August, I rode a horse to Merkigil and stayed in Moníka’s house. The trip was organized by my friends Fjóla and Elvar from Syðra-Skörðugil (from whom I bought my first Icelandic horse 25 years ago, as you can read in A Good Horse Has No Color). A few months before, on Fjóla’s recommendation, I bought and read Moníka’s biography, Konan í Dalnum og Dæturnar Sjö (The Woman in the Valley and her Seven Daughters) by Guðmundur G. Hagalin. There I learned these things about Moníka’s remarkable life:

In 1924, Moníka was working in a fish factory in Reykjavík when she received a letter. We would call it a love letter. She wasn’t so sure.

Moníka was then 23, the seventh child of 10 from the little farm of Ánastaðir in Skagafjörður, north Iceland. She was small, sturdy, and powerful, and known as a hard worker. At the young age of 11, she had left home to go to work, spinning, milking, making hay, and caring for animals, children, and old folks at various farms in the district, where she earned a reputation as a young woman you could count on. Then she had followed her two sisters to Reykjavík, where their uncle was foreman at a fish factory, and joined thirty-some other women cleaning and salting fish; her record was 3,000 fish in a day—she found it boring to not work as hard as she could. But she also liked having her evenings free, when the work day was over, and having money in her pocket to buy pretty clothes and enjoy the city, plus more put aside to bring home to her family when she visited them, as she was planning to do that summer.

Then she got the letter. When she was 11, her very first summer away from home, she had worked at haymaking with a boy named Johannes; he was about 14. The two of them had been sent off to a nearby farm his father had leased and told to hay it; they cut the grass with a scythe, raked it until it was dry, bagged it up into bales, and transported home 40 horse-loads of fine hay.

Never have I forgotten that summer we made hay, the letter read. It was from Johannes. He and his parents now owned half of a farm named Merkigil, deep in one of the valleys of Skagafjörður. His mother was ill, he said, and he wondered if Moníka could come to Merkigil and take charge of the household. Moníka, too, remembered their hay-making. She had become quite fond of Johannes, who was funny and easy-going and hard-working; she recalled how quiet it was in the evenings, as they walked home side by side, satisfied with their day’s accomplishments. What is he really asking me, she wondered. She put off replying to his letter until, finally, it seemed pointless to do so: He must have found someone else by now, she thought.

She took the boat home, where she immediately ran into a neighbor who said, If you were a man, I’d have a job for you.

And what job, Moníka asked, do you have that only a man can do?

He needed someone to cut, dry, bale, and transport seventy horse-loads of hay, and he was willing to pay well.

I’ll do it, she said. And she did. She visited her parents for a few days, then took a tent, went up to the hayfield with a scythe and a rake, and started making hay. It took her five weeks. When the haymaking was over, she packed up her things and prepared to return to Reykjavík. But the boat was late, and she had to wait several days in the harbor town. While she was there, she was accosted by a man named Gísli, who had been searching all over for her, he said. He had a job that only she could do. He needed someone who could work hard, both inside the house and on the farm, and who was also a good nurse, for there was an old, sick couple who desperately needed help. His sister was with them now, but she couldn’t stay.

And where is this farm? Moníka asked, and was startled when he replied: Merkigil. Almost in spite of herself, she found herself saying yes. Gísli gave her no time to change her mind. He had four strong horses with him, and they set off at once to ride the 50 miles to Merkigil. Late in the evening, they reached the treacherous gorge.

You’re not afraid of heights, I hope, Gísli said.

Of course not, said Moníka, though she paused on the brink of the cliff, and looked down into the deep, dark gorge, its bottom hidden in the shadows. They got off their horses and led them down the switchbacked trail, which was snow-covered and a little icy in places, herding their two extra horses ahead of them. They crossed the rocky stream at the bottom, and climbed up the steep slope on the other side.

Caption: In 2022, I crossed the Merkigil gorge in the opposite direction, on a brilliant summer day. It was still scary. Here we are on the brink, watching our loose horses climb the opposite wall of the canyon. Caption: The gorge stretching out below us as we climb and climb. Caption: I got an assist from the tail ahead of me. Caption: Finally we reached the top. A short ride ahead was a cluster of buildings with grass roofs: the barns and houses of Merkigil. Gísli’s sister was delighted to see him and Moníka, when they arrived that night in 1924. She introduced Moníka to 93-year-old Sigurbjörg, who was bed-ridden, and her slightly more vigorous husband, Egill. Then she took Moníka next door to the main living room, where she would sleep. There she was greeted by Johannes and his father, and by Johannes’s mother, who was also bed-ridden. So you have come, she said, thank heavens.

No one said anything about Johannes’s letter, but two years later he and Moníka married. They had eight children—seven daughters and one son—and then, in 1944, Johannes died of cancer. By then, the whole farm was theirs, and the loans were all paid off. They had three milk cows, some steers, 200 sheep, eight riding horses, three breeding horses, and some untrained foals. The fields were in good shape and well-fenced. Moníka decided to stay and run Merkigil with her children.

Her oldest daughter, Elín, was then 19; she took charge of the sheep. She and her sister Margrét, 17, also did the haymaking, when recurring stomach pains kept Moníka from doing it. They were helped by Jóhanna, 16, and Guðrún, 14. All went well, in general—except when sheep got lost in the fog and horses fell into the canyon and had to be rescued. Moníka’s biggest aggravation was that the house, a traditional wooden frame clad with turf blocks, was falling down around their ears. Turf houses need a lot of maintenance, and the work is heavy and takes some skill. With the help of neighbors, she cut and dried new turf and repaired the walls as best they could, but by 1948 Moníka had decided it was time to build a modern, concrete house.

The house she designed was two stories tall, with high ceilings and wide windows. She took out a loan, hired a team of housebuilders, and bought building materials, having them trucked as far as the road went, past the neighboring farm of Gilsbakki. Then she and her daughters loaded everything onto horseback—wood for the concrete forms, roofing panels, window glass, doors, a kitchen stove, a bathtub—and conveyed them down the switchbacked trail into Merkigil gorge and up again to the new house site.

The hardest thing to carry was the cement mixer, but Moníka’s daughters were determined to figure out a way—otherwise, they knew, they’d be the ones mixing the cement by hand—and they succeeded. Then, to save themselves a little more work, they rigged up a motor for it: They wrapped a long rope around the drum of the mixer, and secured it to a horse, which one of the younger children led away. Once the horse reached the end of the rope, the cement was mixed and ready to pour.

By 1950, the house was finished, inside and out. Three years later, Moníka was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of the Falcon by the president of Iceland, for her services to the nation. She was the first woman so honored. At first she was dumbfounded. Why was a simple housewife and farmer being given this honor? Then she thought about it. As she told her daughters, I suppose I deserve it as much as anyone does. You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

This August, I rode a horse to Merkigil and stayed in Moníka’s house. The trip was organized by my friends Fjóla and Elvar from Syðra-Skörðugil (from whom I bought my first Icelandic horse 25 years ago, as you can read in A Good Horse Has No Color). A few months before, on Fjóla’s recommendation, I bought and read Moníka’s biography, Konan í Dalnum og Dæturnar Sjö (The Woman in the Valley and her Seven Daughters) by Guðmundur G. Hagalin. There I learned these things about Moníka’s remarkable life:

In 1924, Moníka was working in a fish factory in Reykjavík when she received a letter. We would call it a love letter. She wasn’t so sure.

Moníka was then 23, the seventh child of 10 from the little farm of Ánastaðir in Skagafjörður, north Iceland. She was small, sturdy, and powerful, and known as a hard worker. At the young age of 11, she had left home to go to work, spinning, milking, making hay, and caring for animals, children, and old folks at various farms in the district, where she earned a reputation as a young woman you could count on. Then she had followed her two sisters to Reykjavík, where their uncle was foreman at a fish factory, and joined thirty-some other women cleaning and salting fish; her record was 3,000 fish in a day—she found it boring to not work as hard as she could. But she also liked having her evenings free, when the work day was over, and having money in her pocket to buy pretty clothes and enjoy the city, plus more put aside to bring home to her family when she visited them, as she was planning to do that summer.

Then she got the letter. When she was 11, her very first summer away from home, she had worked at haymaking with a boy named Johannes; he was about 14. The two of them had been sent off to a nearby farm his father had leased and told to hay it; they cut the grass with a scythe, raked it until it was dry, bagged it up into bales, and transported home 40 horse-loads of fine hay.

Never have I forgotten that summer we made hay, the letter read. It was from Johannes. He and his parents now owned half of a farm named Merkigil, deep in one of the valleys of Skagafjörður. His mother was ill, he said, and he wondered if Moníka could come to Merkigil and take charge of the household. Moníka, too, remembered their hay-making. She had become quite fond of Johannes, who was funny and easy-going and hard-working; she recalled how quiet it was in the evenings, as they walked home side by side, satisfied with their day’s accomplishments. What is he really asking me, she wondered. She put off replying to his letter until, finally, it seemed pointless to do so: He must have found someone else by now, she thought.

She took the boat home, where she immediately ran into a neighbor who said, If you were a man, I’d have a job for you.

And what job, Moníka asked, do you have that only a man can do?

He needed someone to cut, dry, bale, and transport seventy horse-loads of hay, and he was willing to pay well.

I’ll do it, she said. And she did. She visited her parents for a few days, then took a tent, went up to the hayfield with a scythe and a rake, and started making hay. It took her five weeks. When the haymaking was over, she packed up her things and prepared to return to Reykjavík. But the boat was late, and she had to wait several days in the harbor town. While she was there, she was accosted by a man named Gísli, who had been searching all over for her, he said. He had a job that only she could do. He needed someone who could work hard, both inside the house and on the farm, and who was also a good nurse, for there was an old, sick couple who desperately needed help. His sister was with them now, but she couldn’t stay.

And where is this farm? Moníka asked, and was startled when he replied: Merkigil. Almost in spite of herself, she found herself saying yes. Gísli gave her no time to change her mind. He had four strong horses with him, and they set off at once to ride the 50 miles to Merkigil. Late in the evening, they reached the treacherous gorge.

You’re not afraid of heights, I hope, Gísli said.

Of course not, said Moníka, though she paused on the brink of the cliff, and looked down into the deep, dark gorge, its bottom hidden in the shadows. They got off their horses and led them down the switchbacked trail, which was snow-covered and a little icy in places, herding their two extra horses ahead of them. They crossed the rocky stream at the bottom, and climbed up the steep slope on the other side.

Caption: In 2022, I crossed the Merkigil gorge in the opposite direction, on a brilliant summer day. It was still scary. Here we are on the brink, watching our loose horses climb the opposite wall of the canyon. Caption: The gorge stretching out below us as we climb and climb. Caption: I got an assist from the tail ahead of me. Caption: Finally we reached the top. A short ride ahead was a cluster of buildings with grass roofs: the barns and houses of Merkigil. Gísli’s sister was delighted to see him and Moníka, when they arrived that night in 1924. She introduced Moníka to 93-year-old Sigurbjörg, who was bed-ridden, and her slightly more vigorous husband, Egill. Then she took Moníka next door to the main living room, where she would sleep. There she was greeted by Johannes and his father, and by Johannes’s mother, who was also bed-ridden. So you have come, she said, thank heavens.

No one said anything about Johannes’s letter, but two years later he and Moníka married. They had eight children—seven daughters and one son—and then, in 1944, Johannes died of cancer. By then, the whole farm was theirs, and the loans were all paid off. They had three milk cows, some steers, 200 sheep, eight riding horses, three breeding horses, and some untrained foals. The fields were in good shape and well-fenced. Moníka decided to stay and run Merkigil with her children.

Her oldest daughter, Elín, was then 19; she took charge of the sheep. She and her sister Margrét, 17, also did the haymaking, when recurring stomach pains kept Moníka from doing it. They were helped by Jóhanna, 16, and Guðrún, 14. All went well, in general—except when sheep got lost in the fog and horses fell into the canyon and had to be rescued. Moníka’s biggest aggravation was that the house, a traditional wooden frame clad with turf blocks, was falling down around their ears. Turf houses need a lot of maintenance, and the work is heavy and takes some skill. With the help of neighbors, she cut and dried new turf and repaired the walls as best they could, but by 1948 Moníka had decided it was time to build a modern, concrete house.

The house she designed was two stories tall, with high ceilings and wide windows. She took out a loan, hired a team of housebuilders, and bought building materials, having them trucked as far as the road went, past the neighboring farm of Gilsbakki. Then she and her daughters loaded everything onto horseback—wood for the concrete forms, roofing panels, window glass, doors, a kitchen stove, a bathtub—and conveyed them down the switchbacked trail into Merkigil gorge and up again to the new house site.

The hardest thing to carry was the cement mixer, but Moníka’s daughters were determined to figure out a way—otherwise, they knew, they’d be the ones mixing the cement by hand—and they succeeded. Then, to save themselves a little more work, they rigged up a motor for it: They wrapped a long rope around the drum of the mixer, and secured it to a horse, which one of the younger children led away. Once the horse reached the end of the rope, the cement was mixed and ready to pour.

By 1950, the house was finished, inside and out. Three years later, Moníka was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of the Falcon by the president of Iceland, for her services to the nation. She was the first woman so honored. At first she was dumbfounded. Why was a simple housewife and farmer being given this honor? Then she thought about it. As she told her daughters, I suppose I deserve it as much as anyone does. You can read more about Iceland and my many adventures there in my new book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, which will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon & Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Wednesday, April 6, 2022

How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth

Icelanders believe in elves. Does that make you laugh?

I used to find it funny too. I used to think Icelanders who spoke of elves were playing tricks, poking fun, talking tongue-in-cheek, telling tall tales.

Then I met Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir, a well-known elf-seer. We took a walk in a lava field she and her elf friends had protected from destruction when a new road was built nearby. We didn't talk much about elves or the Hidden Folk as we walked. Instead, we photographed lava crags and stacks and pillars, pillows of silver-green moss, caves and clefts and individual lichen-splashed rocks. It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

We wandered about pointing out plants. I didn’t keep a list, but two hours later, back at my hotel when I wrote up my recollections, I remembered blueberry, crowberry, stone bramble, violet, dandelion, mountain avens, buttercup, butterwort, wood geranium, wild thyme, willow shrubs with pale fluffy catkins, and several kinds of grass, including sheep’s sorrel, which we tasted—it was sour as limes. Elves’ cup moss was the only sign of elves I saw.

We listened to the wind sighing in the knee-high willows and the incessant cries of seabirds: black-backed gulls barking now! now! now! and arctic terns, many terns, with their piercing kree-yah cries.

We talked about art and inspiration. What is inspiration? Why do some places attract artists and spark creative thought? Why are some places beautiful—and how do you define beauty?

And we shared an experience I still can't explain.

Said Ragnhildur, as we left the lava field, "Now do you believe in elves?" In my next book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

Illuminated by my encounters with Iceland's Otherworld over the last 35 years—in ancient lava fields, on a holy mountain, beside a glacier and an erupting volcano, crossing the cold desert at the island's heart on horseback—Looking for the Hidden Folk offers an intimate conversation about how we look at and find value in nature. It reveals how the words we use and the stories we tell shape the world we see. It argues that our beliefs about the Earth will preserve, or destroy, it.

Scientists name our time the Anthropocene, the Human Age: Climate change will lead to the mass extinction of species unless we humans change course. Iceland suggests a different way of thinking about the Earth, one that to me offers hope. Icelanders believe in elves, and you should too.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I'm currently putting together my book tour, scheduling both online talks and (let's hope) in-person appearances. Let me know at nancymariebrown@gmail.com if you'd like to organize an event to help get the word out about Looking for the Hidden Folk.

I used to find it funny too. I used to think Icelanders who spoke of elves were playing tricks, poking fun, talking tongue-in-cheek, telling tall tales.

Then I met Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir, a well-known elf-seer. We took a walk in a lava field she and her elf friends had protected from destruction when a new road was built nearby. We didn't talk much about elves or the Hidden Folk as we walked. Instead, we photographed lava crags and stacks and pillars, pillows of silver-green moss, caves and clefts and individual lichen-splashed rocks. It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

We wandered about pointing out plants. I didn’t keep a list, but two hours later, back at my hotel when I wrote up my recollections, I remembered blueberry, crowberry, stone bramble, violet, dandelion, mountain avens, buttercup, butterwort, wood geranium, wild thyme, willow shrubs with pale fluffy catkins, and several kinds of grass, including sheep’s sorrel, which we tasted—it was sour as limes. Elves’ cup moss was the only sign of elves I saw.

We listened to the wind sighing in the knee-high willows and the incessant cries of seabirds: black-backed gulls barking now! now! now! and arctic terns, many terns, with their piercing kree-yah cries.

We talked about art and inspiration. What is inspiration? Why do some places attract artists and spark creative thought? Why are some places beautiful—and how do you define beauty?

And we shared an experience I still can't explain.

Said Ragnhildur, as we left the lava field, "Now do you believe in elves?" In my next book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

Illuminated by my encounters with Iceland's Otherworld over the last 35 years—in ancient lava fields, on a holy mountain, beside a glacier and an erupting volcano, crossing the cold desert at the island's heart on horseback—Looking for the Hidden Folk offers an intimate conversation about how we look at and find value in nature. It reveals how the words we use and the stories we tell shape the world we see. It argues that our beliefs about the Earth will preserve, or destroy, it.

Scientists name our time the Anthropocene, the Human Age: Climate change will lead to the mass extinction of species unless we humans change course. Iceland suggests a different way of thinking about the Earth, one that to me offers hope. Icelanders believe in elves, and you should too.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I'm currently putting together my book tour, scheduling both online talks and (let's hope) in-person appearances. Let me know at nancymariebrown@gmail.com if you'd like to organize an event to help get the word out about Looking for the Hidden Folk.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Down to Earth

Studying the Icelandic sagas, as I noted in a previous essay, is a great way to make a life. It's not, however, easy to earn a living doing so.

For many years, I worked as a science writer and editor at a university magazine to feed my Iceland habit (and myself). Leaving that job in 2003, I found myself writing less and less about science (and getting paid less and less for the magazine articles I did write), and supporting myself more and more by editing.

By accident, I established a niche editing academic papers for scholars who wrote in English as a second (or third) language. No matter the topic, I found it to be satisfying work--it engaged the same part of my brain as the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzles. What was this person thinking, I asked, when she chose this word? this phrase? How could she present her point more succinctly?

Inevitably, Iceland encroached on my editing work. An anthropologist friend who wrote in both languages sent me a copy of his biography of the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson and asked what I thought. I was honest. I critiqued his voice. I told him it bothered me as a reader when he suddenly switched from academic English to colloquial speech.

He was intrigued. Do I do that? he mused.

He asked if I would help him with his then-current project, and I ended up editing and working with him to heavily revise the English edition of The Man Who Stole Himself: The Slave Odyssey of Hans Jonathan. The book was listed in the Times Literary Supplement's Books of the Year and won the Sutlive Prize for the Best Book on Historical Anthropology.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book, Down to Earth, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too.

I'm grateful to Gísli for wanting his voice in English to be as strong as possible, and to his university (the University of Iceland) for providing him with research funds he could use to hire an editor.

Here is a little taste of Down to Earth:

"My first habitat was a small, wooden house on the isle of Heimaey in the Westman Islands, forty-nine square metres in size and built on bare rock that thousands of years ago had been hot lava, welling from deep below the earth's surface. The house had a name: It was called Bolstad. I have always thought Bolstad a fine name: Literally, it means 'habitat.' As my habitat, Bolstad was a microcosm of Heimaey, whose name means 'Home Island.' Bolstad was a place where the future was certain."

Bolstad, he tells us, "succumbed to glowing lava" when a volcano erupted on Heimaey in 1973. Gísli was not there: He was a graduate student in England, and his family had moved to Iceland's mainland.

"We were not among the five thousand refugees fleeing the eruption that night," he writes. "I did not see Bolstad destroyed. But I came across a picture, the final photo of my birthplace, around the time that I began writing this book. I was startled to see it. When I showed it to my siblings and our mother, they reacted the same way I did: shocked and silent.

"Nothing has outmatched Nature here. A light westerly breeze carries off the clouds of steam rising from the lava, giving the photographer a clear view of what once was Bolstad. The advancing lava has already buried one end wall of the house where my mother 'birthed me in the bed,' as she put it. The other end wall has been thrust forward, and the lava has set the house on fire; flames lick the roof and windows. In the heat, the sheet asbestos of the roof has exploded into white flakes, which flutter down like snow onto the black volcanic ash that has settled around the house.

"The bulky television aerial on the roof of Bolstad is still standing; it presumably still picks up a signal from the mainland, but there is no one home to receive it. I gaze at the photo for a long time, my eye drawn again and again to that aerial. Is it a metaphor for the present day?" Is it a warning?

Down to Earth by Gísli Pálsson was published in 2020 by Punctum Books. You can read the ebook for free at https://punctumbooks.com/titles/down-to-earth/. If you like it, please make a donation to this nonprofit publishing house. Their editors have to earn a living (as well as make a life), too.

For more on my latest saga-based project, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

For many years, I worked as a science writer and editor at a university magazine to feed my Iceland habit (and myself). Leaving that job in 2003, I found myself writing less and less about science (and getting paid less and less for the magazine articles I did write), and supporting myself more and more by editing.

By accident, I established a niche editing academic papers for scholars who wrote in English as a second (or third) language. No matter the topic, I found it to be satisfying work--it engaged the same part of my brain as the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzles. What was this person thinking, I asked, when she chose this word? this phrase? How could she present her point more succinctly?

Inevitably, Iceland encroached on my editing work. An anthropologist friend who wrote in both languages sent me a copy of his biography of the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson and asked what I thought. I was honest. I critiqued his voice. I told him it bothered me as a reader when he suddenly switched from academic English to colloquial speech.

He was intrigued. Do I do that? he mused.

He asked if I would help him with his then-current project, and I ended up editing and working with him to heavily revise the English edition of The Man Who Stole Himself: The Slave Odyssey of Hans Jonathan. The book was listed in the Times Literary Supplement's Books of the Year and won the Sutlive Prize for the Best Book on Historical Anthropology.

By that time I was hard at work editing Gísli Pálsson's next book, Down to Earth, which mixes his own memories of growing up next door to a volcano with his critical explorations, as an anthropologist, into the Anthropocene, the geological era defined by humans' growing impact on the earth. In many ways, this book was my perfect editing project: merging Iceland, science (volcanology, seismology, anthropology), and history. I'm sure there's a mention of the Icelandic sagas in there somewhere, too.

I'm grateful to Gísli for wanting his voice in English to be as strong as possible, and to his university (the University of Iceland) for providing him with research funds he could use to hire an editor.

Here is a little taste of Down to Earth:

"My first habitat was a small, wooden house on the isle of Heimaey in the Westman Islands, forty-nine square metres in size and built on bare rock that thousands of years ago had been hot lava, welling from deep below the earth's surface. The house had a name: It was called Bolstad. I have always thought Bolstad a fine name: Literally, it means 'habitat.' As my habitat, Bolstad was a microcosm of Heimaey, whose name means 'Home Island.' Bolstad was a place where the future was certain."

Bolstad, he tells us, "succumbed to glowing lava" when a volcano erupted on Heimaey in 1973. Gísli was not there: He was a graduate student in England, and his family had moved to Iceland's mainland.

"We were not among the five thousand refugees fleeing the eruption that night," he writes. "I did not see Bolstad destroyed. But I came across a picture, the final photo of my birthplace, around the time that I began writing this book. I was startled to see it. When I showed it to my siblings and our mother, they reacted the same way I did: shocked and silent.

"Nothing has outmatched Nature here. A light westerly breeze carries off the clouds of steam rising from the lava, giving the photographer a clear view of what once was Bolstad. The advancing lava has already buried one end wall of the house where my mother 'birthed me in the bed,' as she put it. The other end wall has been thrust forward, and the lava has set the house on fire; flames lick the roof and windows. In the heat, the sheet asbestos of the roof has exploded into white flakes, which flutter down like snow onto the black volcanic ash that has settled around the house.

"The bulky television aerial on the roof of Bolstad is still standing; it presumably still picks up a signal from the mainland, but there is no one home to receive it. I gaze at the photo for a long time, my eye drawn again and again to that aerial. Is it a metaphor for the present day?" Is it a warning?

Down to Earth by Gísli Pálsson was published in 2020 by Punctum Books. You can read the ebook for free at https://punctumbooks.com/titles/down-to-earth/. If you like it, please make a donation to this nonprofit publishing house. Their editors have to earn a living (as well as make a life), too.

For more on my latest saga-based project, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

The Museum You Will Never See

It's rare that I read a book about "my" Iceland, a book that captures the mix of place and people, nature and culture, history and saga that make Iceland my intellectual homeland. It's even rarer when one of these books is written by a non-Icelander.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, by A. Kendra Greene, is one of these special books, and the best I have found in a long time. Her description of stones first drew me in, when an excerpt from the book was published on LitHub; I read:

"When I say stone, perhaps I should clarify that I do not mean some plain-Jane piece of rock. I mean eye-catching. I mean white whisker-width spines radiating out in clusters like so many cowlicks. I mean a green between celery and mustard, pocked with pinprick bubbles and skimming like a rind over a vein that's crystal clear at the edges but clotting in the middle to the color of cream stirred into weak tea. I mean crystals like a jumble of molars and I mean jasper in oxblood and ocher and clover and sky, sometimes a hunk of one color but more likely a blend of two or three or five, maybe like ice creams melting together, or perhaps like cards stacked in a deck."

Here is a writer describing the indescribable, a writer reaching for words--it's like, it's like, what is it like?--and failing and trying again and, by her persistence, forcing me to see these rocks so clearly that by the end of the paragraph I am holding them in my mind's hand and setting them on the shelf of my own Icelandic rock collection. By the end of the paragraph, I had purchased the book.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open.

I've been visiting Iceland since 1986. Soon after 2008, I noticed a change: little museums were sprouting up everywhere. It seemed as if the Icelanders' response to the global monetary crisis was to rummage through their closets and attics and rediscover their culture--or that their response to the "tourist eruption," after the real eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, was to corral the crowds into a museum, both to harvest their cash and to keep them from straggling all over the farm or town and getting in the way of real life.

Several of the little museums Greene explores are older than the crash. The Penis Museum dates from 1997, I learned. I've never been. I thought it was tacky; it's not. As Greene explains it, it's rather remarkable. Like many things in Iceland, it started as a joke that got out of hand and ended up being a philosophical inquiry.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.") There's also a lovely array of children's bone toys:

According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is itself a museum, a collection of long articles and short essays, illustrations, lists. As a writer Greene is as observant about the Icelandic friends she makes and the historical people she researches as she is about the stones preserved in their collections. Alongside her long investigations of the penis museum, the stone museum, the bird museum, the folk museum, the witchcraft museum, the sea monster museum, and the herring museum, she includes several cabinets of curiosities, vignettes of collectors and their collections and the haphazard links between them. There's "The Museum of the Story I Heard," for instance, and "The Museum of Darkness," and "The Museum of Obligation," of which she writes: "I love this story of undaunted independence, of artistic freedom, of doubling down, of sticking it to the man. But there is a way of telling it that is all about obligation, a telling that is almost meek." And so she frames the story of this one-man museum again, and we realise the first picture she painted was merely the reflection of the place in a puddle.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, and Other Excursions to Iceland's Most Unusual Museums, by A. Kendra Greene, was published in 2020 by Penguin Books. My only complaint is that the text is printed in hard-to-read light blue ink. But I think you'll persevere.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is one of several books about Iceland that I recommend on my Bookshop at https://bookshop.org/shop/nancymariebrown. For more on my own latest Iceland-related project, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, see the related posts on this blog (click here) or my page at Macmillan.com.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and may earn a commission if you click through and purchase the books mentioned here.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, by A. Kendra Greene, is one of these special books, and the best I have found in a long time. Her description of stones first drew me in, when an excerpt from the book was published on LitHub; I read:

"When I say stone, perhaps I should clarify that I do not mean some plain-Jane piece of rock. I mean eye-catching. I mean white whisker-width spines radiating out in clusters like so many cowlicks. I mean a green between celery and mustard, pocked with pinprick bubbles and skimming like a rind over a vein that's crystal clear at the edges but clotting in the middle to the color of cream stirred into weak tea. I mean crystals like a jumble of molars and I mean jasper in oxblood and ocher and clover and sky, sometimes a hunk of one color but more likely a blend of two or three or five, maybe like ice creams melting together, or perhaps like cards stacked in a deck."

Here is a writer describing the indescribable, a writer reaching for words--it's like, it's like, what is it like?--and failing and trying again and, by her persistence, forcing me to see these rocks so clearly that by the end of the paragraph I am holding them in my mind's hand and setting them on the shelf of my own Icelandic rock collection. By the end of the paragraph, I had purchased the book.

I've done this before, purchased a book on the strength of a paragraph, but this time I was not disappointed one bit. The rest of The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is just as honest and careful and reaching and, yes, sometimes failing, and persistent in its desire to share this odd collection of museums (some imaginary) and collectors (some unimaginable) that Greene found by traveling around Iceland with her eyes--and her heart--wide open.

I've been visiting Iceland since 1986. Soon after 2008, I noticed a change: little museums were sprouting up everywhere. It seemed as if the Icelanders' response to the global monetary crisis was to rummage through their closets and attics and rediscover their culture--or that their response to the "tourist eruption," after the real eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in 2010, was to corral the crowds into a museum, both to harvest their cash and to keep them from straggling all over the farm or town and getting in the way of real life.

Several of the little museums Greene explores are older than the crash. The Penis Museum dates from 1997, I learned. I've never been. I thought it was tacky; it's not. As Greene explains it, it's rather remarkable. Like many things in Iceland, it started as a joke that got out of hand and ended up being a philosophical inquiry.

The Folk Museum at Skogar, founded in 1949, is one of my favorite places in Iceland. I described it this way in an earlier blog post: "In addition to a collection of old houses, fully furnished, there's a separate building of several rooms stuffed with what can only be described as, well, stuff. There are books and embroideries and a two-stringed fiddle. There are birds' eggs, skeletons, rocks, pinned insects, pressed flowers, and a stuffed two-headed sheep. There are busts of several local dignitaries and two paintings by one of Iceland's most famous artists, Kjarval, in the basement, along with some mid-20th-century living room furniture and a famous writer's studio. There's a fishing boat. There's an excellent description of how to make spoons from cows' horns." (See "An Icelandic Horse Hair Tale.") There's also a lovely array of children's bone toys:

According to Greene, there are some 15,000 objects at Skogar, displayed in no particular order. "This is a museum without sequence," she writes. "Even the guides say you can start anywhere. It all links, they say." And then she proceeds to prove that bold statement true. "And it's all here, the collection and the curator and the museum and the parking lot and the tour buses and maybe the garden, too, all because this someone in this someplace, a long time ago, was given a quest." Following Greene as she follows this someone on his quest is like taking a little quest of your own through Iceland's fabulous landscape and history.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See is itself a museum, a collection of long articles and short essays, illustrations, lists. As a writer Greene is as observant about the Icelandic friends she makes and the historical people she researches as she is about the stones preserved in their collections. Alongside her long investigations of the penis museum, the stone museum, the bird museum, the folk museum, the witchcraft museum, the sea monster museum, and the herring museum, she includes several cabinets of curiosities, vignettes of collectors and their collections and the haphazard links between them. There's "The Museum of the Story I Heard," for instance, and "The Museum of Darkness," and "The Museum of Obligation," of which she writes: "I love this story of undaunted independence, of artistic freedom, of doubling down, of sticking it to the man. But there is a way of telling it that is all about obligation, a telling that is almost meek." And so she frames the story of this one-man museum again, and we realise the first picture she painted was merely the reflection of the place in a puddle.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, and Other Excursions to Iceland's Most Unusual Museums, by A. Kendra Greene, was published in 2020 by Penguin Books. My only complaint is that the text is printed in hard-to-read light blue ink. But I think you'll persevere.