Icelanders believe in elves. Does that make you laugh?

I used to find it funny too. I used to think Icelanders who spoke of elves were playing tricks, poking fun, talking tongue-in-cheek, telling tall tales.

Then I met Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir, a well-known elf-seer. We took a walk in a lava field she and her elf friends had protected from destruction when a new road was built nearby. We didn't talk much about elves or the Hidden Folk as we walked. Instead, we photographed lava crags and stacks and pillars, pillows of silver-green moss, caves and clefts and individual lichen-splashed rocks.

It was by turns warm and sunny and cloudy and cool, a fine summer’s day. The breeze was light—just enough to keep the gnats at bay. The land smelled of peat, with hints of salt and sea.

We wandered about pointing out plants. I didn’t keep a list, but two hours later, back at my hotel when I wrote up my recollections, I remembered blueberry, crowberry, stone bramble, violet, dandelion, mountain avens, buttercup, butterwort, wood geranium, wild thyme, willow shrubs with pale fluffy catkins, and several kinds of grass, including sheep’s sorrel, which we tasted—it was sour as limes. Elves’ cup moss was the only sign of elves I saw.

We listened to the wind sighing in the knee-high willows and the incessant cries of seabirds: black-backed gulls barking now! now! now! and arctic terns, many terns, with their piercing kree-yah cries.

We talked about art and inspiration. What is inspiration? Why do some places attract artists and spark creative thought? Why are some places beautiful—and how do you define beauty?

And we shared an experience I still can't explain.

Said Ragnhildur, as we left the lava field, "Now do you believe in elves?"

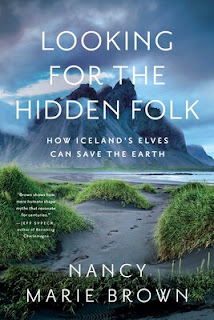

In my next book, Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth, I explore Iceland's "elf question." My quest took me wandering through history, religion, folklore, and art, circling back to explore theology, literary criticism, mythology, and philosophy, stopping along the way to dip my toes into cognitive science, psychology, anthropology, biology, volcanology, cosmology, and quantum mechanics. Each discipline, I found, defines and redefines what is real and unreal, natural and supernatural, demonstrated and theoretical, alive and inert. Each has its own way of perceiving and valuing (or not) the world around us. Each admits its own sort of elf.

Illuminated by my encounters with Iceland's Otherworld over the last 35 years—in ancient lava fields, on a holy mountain, beside a glacier and an erupting volcano, crossing the cold desert at the island's heart on horseback—Looking for the Hidden Folk offers an intimate conversation about how we look at and find value in nature. It reveals how the words we use and the stories we tell shape the world we see. It argues that our beliefs about the Earth will preserve, or destroy, it.

Scientists name our time the Anthropocene, the Human Age: Climate change will lead to the mass extinction of species unless we humans change course. Iceland suggests a different way of thinking about the Earth, one that to me offers hope. Icelanders believe in elves, and you should too.

Looking for the Hidden Folk: How Iceland's Elves Can Save the Earth will be published on October 4 by Pegasus Books. It is now available for pre-order through Simon and Schuster distributors or through my shop on Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I'm currently putting together my book tour, scheduling both online talks and (let's hope) in-person appearances. Let me know at nancymariebrown@gmail.com if you'd like to organize an event to help get the word out about Looking for the Hidden Folk.

Wanderer, storyteller, wise, half-blind, with a wonderful horse.

By Nancy Marie Brown

Showing posts with label Hidden Folk. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hidden Folk. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 6, 2022

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Sami Tales Told "By the Fire"

The Sami of northern Sweden "felt such a personal connection to the trees whose wood they burned, mostly birch and pine, that they chopped 'eyes' in the firewood, so the pieces of wood 'could see they were burning well.'"

I learned this in a delightful book called By the Fire: Sami Folktales and Legends. Collected and illustrated by Emilie Demant Hatt, and translated by Barbara Sjoholm, it includes 70-some tales, along with Demant Hatt's introduction, selections from her fieldnotes, and an essay by Sjoholm.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things.

As a student of comparative literature, I am intrigued by how similar some of Demant Hatt's Sami tales are with other folklore I’m familiar with. For example, Cinderella-type stories are found among the Sami, with evil stepmothers, handsome princes, too-small-slippers that require the chopping off of heels or toes, and all.

As in Icelandic folktales, the Sami speak of Hidden Folk or elves, here called the Haldes. In one story, for example, the evil stepmother tells the girl to spin yarn "at the edge of a gorge, at the bottom of which there was a deep spring. The ball of yarn rolled away from the girl, and when she tried to snatch it, she fell into the spring. But down there she met the good Haldes." The Haldes hire the girl to tend their cows, and eventually let her return home, carrying her wages in gold and silver.

But what I really enjoy reading folktales for are the differences—the things I have not heard before and would not have thought of myself.

Along with the Sami chopping "eyes" in their firewood, for example, in By the Fire I learned about the evil Stallo. A kind of people-eating troll, Stallo "goes around whistling all the time so one can hear when he is in the vicinity. All whistling is taboo among the Sami: the sound of it is absolutely connected with the Evil One and with sorcery."

In Sami language, you can be deaf as Stallo, large as Stallo, or have Stallo's skinny legs. If you had a large head--a small, round head was key to the Sami concept of beauty--you had a Stallo head. If you ate alone, you ate like Stallo. If you had a child with a man you didn't care to marry, that child was Stallo's child.

Stallo also explains the landscape: A single standing stone marks a Stallo grave. A ring of stones is a ruined Stallo tent.

And while Stallo is usually presented as evil, his belt is decorated with a silver star bearing three faces; if you find (or steal) a Stallo-star, you can cure many diseases.

Unlike most folktale collections from the north, as translator Barbara Sjoholm points out, By the Fire contains stories told to Emilie Demant Hatt "as part of other conversations, ethnographic and social, that took place 'by the fire' in tents or turf huts or out in the open air."

Demant Hatt was the first ("and for a long time the only," Sjoholm adds) Scandinavian anthropologist to take an interest in the lives of women and children. Most of the stories she recorded were those that women told among themselves as they worked--sometimes answering Demant Hatt's questions, more often giving conscious performances to entertain the group. In these stories, girls outfox their attackers, girls save their people--and murdered babies come back to haunt their parents.

By the Fire is beautifully illustrated with Demant Hatt's bold and eerie linocuts. Trained as an artist, Demant Hatt first went to northern Sweden in 1904 as a tourist. Inspired by Sami culture, she returned to live with them for many months in 1907. She studied Sami language at the University of Copenhagen, soon becoming fluent, and taught herself ethnography. From 1910 through 1916 she spent her summers with the Sami, first by herself, then bringing along her husband, a graduate student in cultural geography, who sometimes took notes for her while she conducted interviews. Her field notes fill 500 typed pages.

Demant Hatt wrote a memoir of her early adventures, With the Lapps in the High Mountains: A Woman among the Sami, 1907-1908, which has been edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm. Sjoholm also wrote her biography, Black Fox: A Life of Emilie Demant Hatt, Artist and Ethnographer. Two more books to add to my reading list!

For more book recommendations, see my lists at Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I learned this in a delightful book called By the Fire: Sami Folktales and Legends. Collected and illustrated by Emilie Demant Hatt, and translated by Barbara Sjoholm, it includes 70-some tales, along with Demant Hatt's introduction, selections from her fieldnotes, and an essay by Sjoholm.

The nomadic reindeer-herding Sami of the far north often appear in the medieval Icelandic sagas, which provide the source material for most of my own books. The Vikings traded with the Sami for skins, furs, feathers, and walrus ivory, and several Norwegian kings and chieftains forced them to pay tribute--that is, protection money. Sami men and women also appear in the Icelandic sagas as sorcerors and shamans, able to shift their shapes, foretell the future, and find lost things.

As a student of comparative literature, I am intrigued by how similar some of Demant Hatt's Sami tales are with other folklore I’m familiar with. For example, Cinderella-type stories are found among the Sami, with evil stepmothers, handsome princes, too-small-slippers that require the chopping off of heels or toes, and all.

As in Icelandic folktales, the Sami speak of Hidden Folk or elves, here called the Haldes. In one story, for example, the evil stepmother tells the girl to spin yarn "at the edge of a gorge, at the bottom of which there was a deep spring. The ball of yarn rolled away from the girl, and when she tried to snatch it, she fell into the spring. But down there she met the good Haldes." The Haldes hire the girl to tend their cows, and eventually let her return home, carrying her wages in gold and silver.

But what I really enjoy reading folktales for are the differences—the things I have not heard before and would not have thought of myself.

Along with the Sami chopping "eyes" in their firewood, for example, in By the Fire I learned about the evil Stallo. A kind of people-eating troll, Stallo "goes around whistling all the time so one can hear when he is in the vicinity. All whistling is taboo among the Sami: the sound of it is absolutely connected with the Evil One and with sorcery."

In Sami language, you can be deaf as Stallo, large as Stallo, or have Stallo's skinny legs. If you had a large head--a small, round head was key to the Sami concept of beauty--you had a Stallo head. If you ate alone, you ate like Stallo. If you had a child with a man you didn't care to marry, that child was Stallo's child.

Stallo also explains the landscape: A single standing stone marks a Stallo grave. A ring of stones is a ruined Stallo tent.

And while Stallo is usually presented as evil, his belt is decorated with a silver star bearing three faces; if you find (or steal) a Stallo-star, you can cure many diseases.

Unlike most folktale collections from the north, as translator Barbara Sjoholm points out, By the Fire contains stories told to Emilie Demant Hatt "as part of other conversations, ethnographic and social, that took place 'by the fire' in tents or turf huts or out in the open air."

Demant Hatt was the first ("and for a long time the only," Sjoholm adds) Scandinavian anthropologist to take an interest in the lives of women and children. Most of the stories she recorded were those that women told among themselves as they worked--sometimes answering Demant Hatt's questions, more often giving conscious performances to entertain the group. In these stories, girls outfox their attackers, girls save their people--and murdered babies come back to haunt their parents.

By the Fire is beautifully illustrated with Demant Hatt's bold and eerie linocuts. Trained as an artist, Demant Hatt first went to northern Sweden in 1904 as a tourist. Inspired by Sami culture, she returned to live with them for many months in 1907. She studied Sami language at the University of Copenhagen, soon becoming fluent, and taught herself ethnography. From 1910 through 1916 she spent her summers with the Sami, first by herself, then bringing along her husband, a graduate student in cultural geography, who sometimes took notes for her while she conducted interviews. Her field notes fill 500 typed pages.

Demant Hatt wrote a memoir of her early adventures, With the Lapps in the High Mountains: A Woman among the Sami, 1907-1908, which has been edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm. Sjoholm also wrote her biography, Black Fox: A Life of Emilie Demant Hatt, Artist and Ethnographer. Two more books to add to my reading list!

For more book recommendations, see my lists at Bookshop.org. Disclosure: As an affiliate of Bookshop.org, I may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)